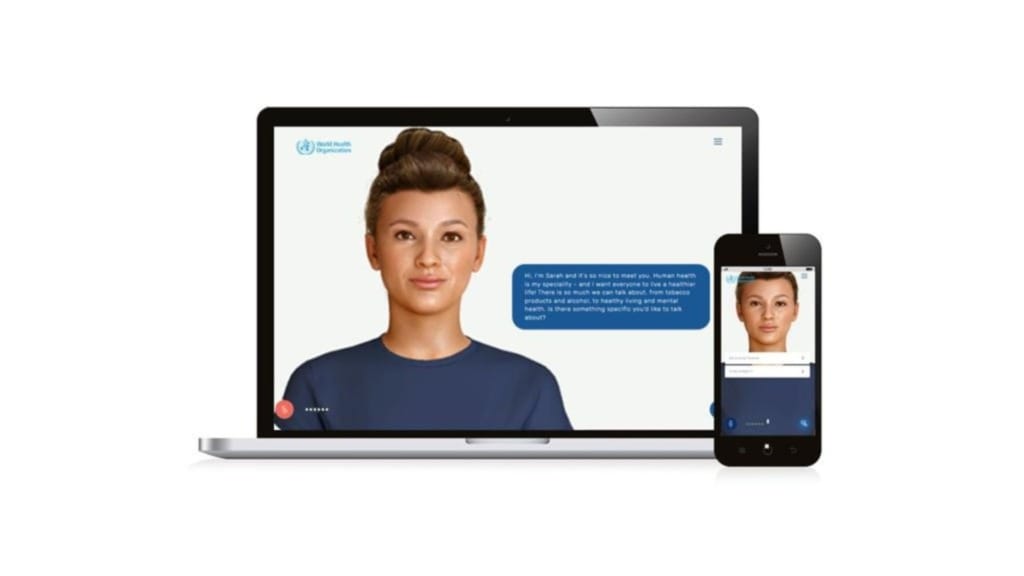

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has embarked on an innovative project using artificial intelligence to disseminate basic health information via a human-like avatar. This venture introduces SARAH, a virtual health assistant designed to offer 24/7 support in eight languages on topics such as mental health and nutrition. However, the WHO cautions on its website that this early prototype, launched on April 2, might not always deliver precise answers.

Challenges with current AI technology

SARAH, or Smart AI Resource Assistant for Health, cannot diagnose, similar to platforms like WebMD or Google. Instead, it directs users to WHO resources or advises consulting with healthcare providers. Despite its empathetic design, SARAH’s responses can sometimes be misleading due to its outdated training data and the inherent limitations of its AI model, which include generating incorrect or “hallucinated” answers.

Ramin Javan, a radiologist and researcher at George Washington University, remarked, “It lacks depth, but I think it’s because they just don’t want to overstep their boundaries, and this is just the first step.” WHO asserts that SARAH is meant to complement the work of human health professionals rather than replace them.

AI’s potential and pitfalls

Trained on OpenAI’s ChatGPT 3.5 with data up to September 2021, SARAH does not have information on more recent medical developments or advisories. For example, it incorrectly stated that the Alzheimer’s drug Lecanemab was still in clinical trials, although it was approved in January 2023 for early disease treatment. Even WHO’s latest statistics can confound SARAH, requiring multiple prompts to fetch the correct information.

In its efforts to simulate empathy, SARAH analyses users’ facial expressions for 30 seconds before deleting this data, ensuring anonymity. WHO’s communications director, Jaimie Guerra, highlights the privacy measures in place to secure these interactions, stating that all sessions are unlinked from any identifiable data to prevent cybersecurity risks.

Future directions and ethical considerations

The development of SARAH builds on WHO’s previous virtual health worker, Florence, and involves the same New Zealand-based company, Soul Machines, for the creation of the avatars. While the current avatar appears white, there is potential for users to select from a variety of avatars in future iterations to enhance personalisation.

WHO recently issued ethical guidelines for the use of AI in health care, emphasising data transparency and user safety. As AI continues to evolve, the integration of these technologies in public health remains a delicate balance between innovation and accuracy.